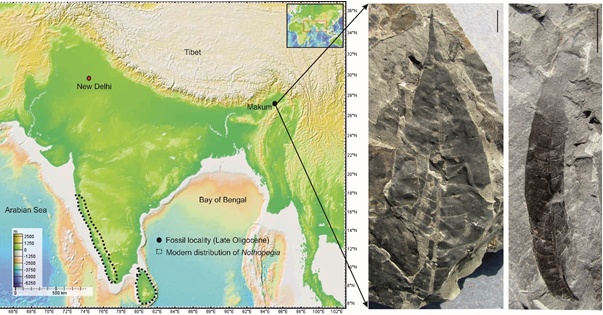

A groundbreaking paleontological discovery in Assam’s coal-rich Makum region has unveiled the world’s oldest known fossil record of Nothopegia, a tropical plant genus that offers new insights into how India’s biodiversity evolved over millions of years.

The 24-million-year-old fossilized leaves, unearthed by a team of Indian scientists, represent a species now found exclusively in the Western Ghats of southern India—thousands of kilometers away from the discovery site in northeast India.

Ancient Climate Patterns Revealed Through Fossil Evidence

The research, spearheaded by scientists from the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences (BSIP) in Lucknow, was published in the prestigious Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology journal. The discovery provides compelling evidence of how dramatic geological and climatic changes reshaped plant distribution across the Indian subcontinent.

“This discovery not only pushes back the fossil record of Nothopegia but also offers compelling evidence of how massive climatic and geological shifts reshaped the distribution of plant species across the Indian subcontinent,” the research team stated.

The fossilized leaves, preserved in coal seams dating back to the late Oligocene epoch (approximately 24 to 23 million years ago), were identified through meticulous morphological analysis and comparison with modern herbarium specimens.

Himalayan Formation Triggered Species Migration

During the Oligocene and Miocene epochs, the collision between the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates triggered the dramatic rise of the Himalayas. This geological upheaval fundamentally altered regional climate patterns, cooling northeast India and disrupting the warm, humid tropical ecosystems that once flourished there.

Climate reconstruction using the Climate Leaf Analysis Multivariate Program (CLAMP) revealed that ancient northeast India experienced conditions similar to today’s Western Ghats—warm and humid environments ideal for tropical species like Nothopegia.

As climatic conditions became cooler and drier in the northeast, Nothopegia disappeared from the region. However, the species survived in the climatically stable Western Ghats, where it continues to thrive as a living relic of India’s ancient biodiversity.

Bridging Past and Present Biodiversity Challenges

“This is more than just a fossil discovery,” explained co-author Dr. Harshita Bhatia. “It’s a story about survival, extinction, and resilience over millions of years—one that resonates with the biodiversity crisis we face today.”

The study demonstrates how paleobotany, plant systematics, and climate modeling can work together to trace the complex history of species migration and extinction patterns across geological time scales.

Conservation Implications for Modern India

The findings underscore the critical importance of preserving biodiversity hotspots like the Western Ghats, which serve as crucial refuges for ancient and vulnerable plant lineages. As current climate change accelerates at unprecedented rates, understanding historical patterns becomes essential for conservation planning.

The research offers valuable insights into how plant species may adapt to—or disappear under—changing environmental conditions, providing a scientific foundation for biodiversity conservation efforts across India and beyond.

Scientific Methodology and Significance

The Makum Coalfield discovery represents a significant advancement in understanding South Asia’s paleobotanical history. The research team’s comprehensive approach, combining fossil analysis with modern climate modeling, sets a new standard for tracing ancient biodiversity patterns.